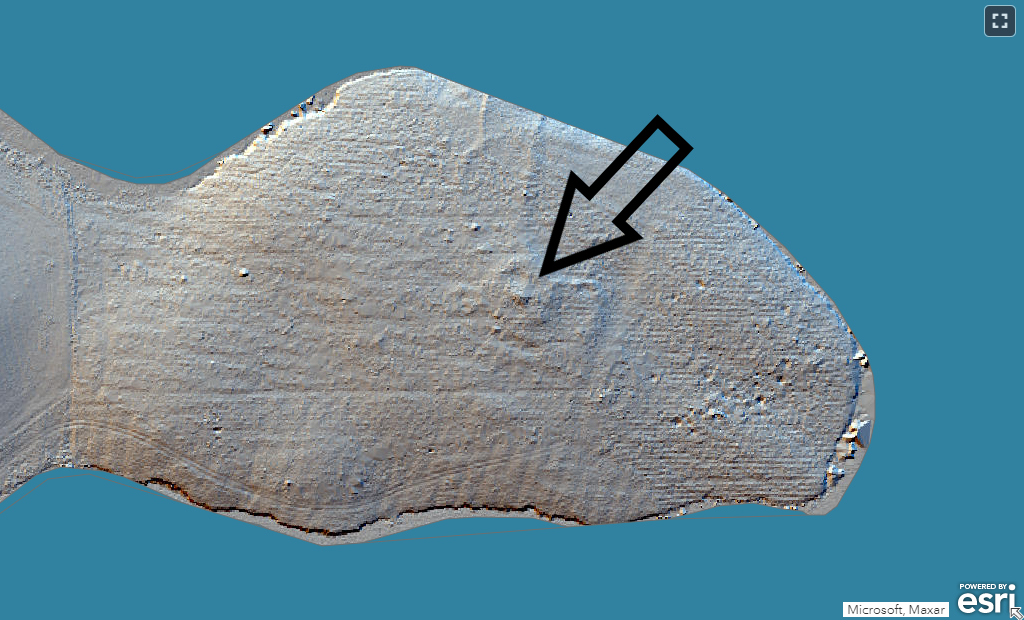

In March, a small team set out to explore a possible new site: an anomaly in the LiDAR data (below) was interpreted as a possible cairn, so we headed out to investigate.

The site is located on a promontory in Whiteadder Reservoir. However, assuming that our site is prehistoric, it would not have been on the shore of a body of water when it was constructed: the reservoir was flooded in 1968. Prior to that, the site’s location was a low hill in the heart of a valley. The site is now under forestry but this was planted sometime after the mid 19th century.

We excavated two trenches: Trench 1 was 2m x 2m, placed roughly in the centre of the site; and Trench 2 was 1m x 6m, running broadly N-S across the northern side of the site with the intention of catching the edge of the cairn material. Through excavating these trenches, we aimed to explore the nature, condition and date of the site.

It became apparent very quickly on removing the overlying carpet of pine needles and organic material that we were coming down on a body of stone, and before too long we were sure that we were indeed excavating a cairn. Any doubts that we may have had about the antiquity of the site were dispersed when Jess discovered a lovely large sherd of prehistoric pottery. Not long after this, Leanne discovered a gorgeous little flint – perhaps the tip of a blade? – and a possible coarse stone tool.

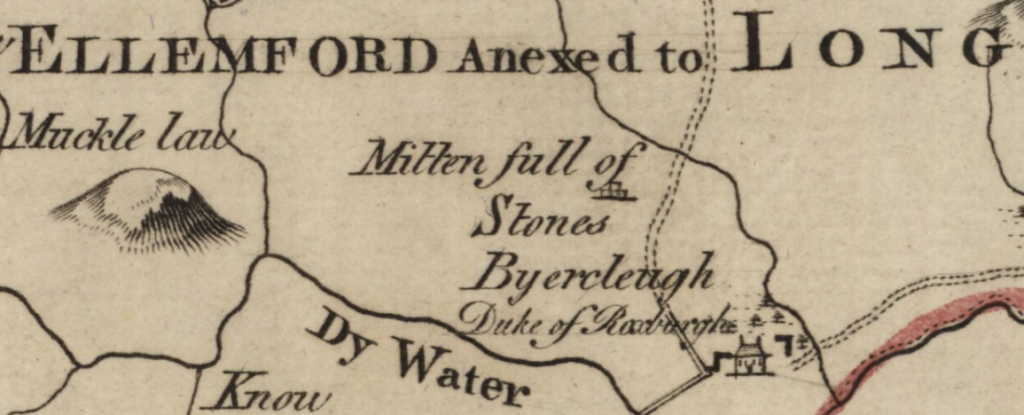

We found no discernible structure within the cairn material, simply a mass of stones in no particular order. This suggests that we are not looking at a Neolithic chambered cairn, since we would expect to have found some evidence of walls within the cairn material either in the central trench, where we might have chanced upon a chamber, or in the long trench over the side, where we might have expected to identify the remains of polycope walls. Although most cairns appear today as large mounds of rubble, many were in fact tiered in profile. Indeed, the long cairn known as the Mutiny Stones, some 5.5km to the south-west of our site, was depicted as a tiered structure as late as 1771 (below).

© Trustees of the National Library of Scotland

We did identify a possible kerb around the edge of the cairn, albeit slipped from its original position. We also identified a possible trampled surface at the exterior of the cairn, perhaps relating to its construction or use.

In the central trench we confirmed that the cairn material was built directly onto the glacial till and, as a reward for heaving out so many heavy stones, we discovered two further flints, perhaps debitage, at the very lowest level of the cairn material. Less than 1m in depth of cairn material was present on top of the natural, and it seems likely that the cairn is very much reduced from its original form. This is likely to be the result of a combination of stone robbing – there are banks and enclosures nearby, some of which are likely to be post-medieval, and could have been constructed using stone taken from the cairn – and other activities such as the planting of the forestry.

We await the results of the wet sieving to find out whether any of our samples may have produced anything suitable for dating. Our finds specialists will look at the artefacts and this too will help us determine the date of the site. We would expect the cairn to date to either the Neolithic or Bronze Age, although it is not uncommon to find Neolithic cairns with evidence of reuse in the Bronze Age. So, we wait to see what our post-excavation analyses will reveal, safe in the knowledge that we have indeed discovered a new cairn.

Many thanks to those who participated in this project with us. Outdoor/face to face activities are of course on hold for now, in line with government advice during the COVID-19 outbreak. We will keep you posted on other opportunities for engagement with the project in the coming weeks and months.