Place-names near the Whiteadder Water: messages from the past

Throughout the project our resident place-names expert, Liz Curtis has been digging into the derivations of the Whiteadder area and finding some fantastic little nuggets of information.

You can listen to a few of the names below and also read some of the research paper. We are also producing a short booklet to document all the findings, which you will soon be able to download from this page.

Over the few thousand years since the last ice age, people have travelled up the Whiteadder valley, some settling, some moving on. They have left traces on the landscape – cairns, stone circles, ramparts, field systems, ruined buildings. They have also left place-names, which can tell us what languages people spoke and how they saw and used the land.

Our earliest name is probably that of the river itself, the Adder, from a pre-Celtic word meaning ‘watercourse’. Both the Whiteadder and the Blackadder, which joins it, were originally just called Adder – the colours were added later, to distinguish them.

During the first millennium BC, the people we call Britons arrived, settling throughout Britain. They were farmers and herders and spoke Brittonic, a Celtic language which is the forerunner of Welsh. A few of their place-names survive in our area, including Monynut, the name of the ridge that runs east of the Whiteadder. This is probably from monid (pronounced mun-ith), meaning ‘hill, upland, or range of hills’, with a river-name Net, perhaps the earlier name of the Monynut Water. Net may mean ‘brilliant, sparkling’.

Most of the Brittonic names are on the northern fringe of our area, suggesting that Britons were pushed away from the better land by later settlers. Garvald is probably from Brittonic garv-alt, ‘rough height’. This may have been the name of the hill-fort which can still be seen at Garvald Mains. The Papana Water’s name may be from pol-i-pant, ‘stream in the valley bottom’. Papple may be from pobil, ‘tents or a camp’, referring to a place where people gathered seasonally, for activities related to livestock. Carfrae is from caer ‘fort’ and bre ‘hill’: the fort has long since been ploughed away, but its ramparts can be seen as cropmarks in aerial photographs. There is another Carfrae, also a fort site, a few miles away in Lauderdale.

From the fifth century AD, Anglo-Saxons landed in Britain from the continent. Their most northerly kingdom was Northumbria, north of the Humber estuary. They expanded further north from the seventh century, taking control of what is now Lothian. They spoke a northern variety of Old English which later developed into Scots.

The Northumbrians established farm settlements along the lower reaches of the Whiteadder. These included Preston, ‘farm of the priests’, from Old English tūn ‘substantial farm’ and prēost ‘priest’. Paxton was ‘Pace’s farm’, containing the rare personal name Pace. Quixwood was ‘Cwic’s enclosure’ from the Old English personal name Cwic and worð (pronounced worth) ‘an enclosure’. Hutton is ‘farm on a projecting ridge’, from hōh-tūn, probably referring to the steep bank on which Hutton Castle sits.

Other Old English place-names reflecting landscape features include Chirnside, ‘a churn(-shaped) hillside’, from cyrn and sīde. Spartleton, the biggest hill in the Lammermuirs east of the Whiteadder, may have invoked another utensil: it may be ‘basket(-shaped) hill’ from sperte ‘basket’ with hyll ‘hill’, and Scots doun ‘hill’ added later. Duns was probably simply from dūn ‘hill’.

Two names have bird associations: Cranshaws was ‘a small wood associated with cranes’, from cran and sceaga, while Foulden was ‘bird valley’, from fugel and denu, probably referring to the deep valley or dean through which the Deans Burn flows.

Vegetation also features. Ellem means ‘at the elder trees’, from Old English ellen, in the dative plural form ellum. Auchencrow, spelt Aldenegraue in 1207, was either ‘old grove’, from ald and grǣfe, or ‘old trench’, from ald and græf.

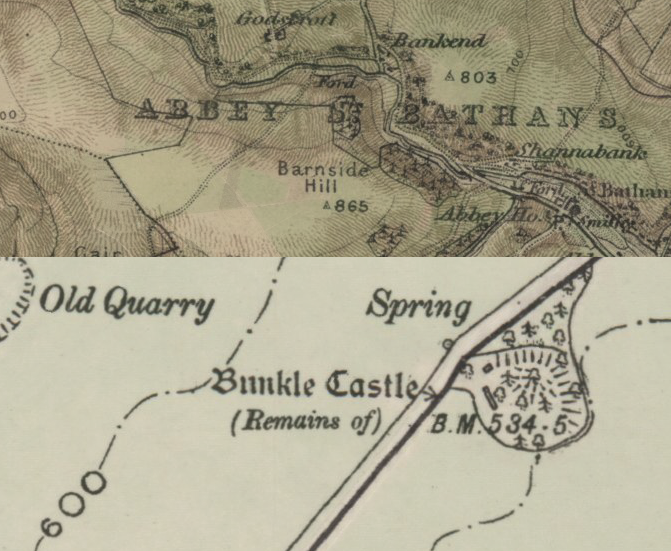

Gaelic-speakers did not penetrate the Lammermuirs in numbers, but place-name evidence suggests that Gaelic-speaking monks passed along the Whiteadder valley in the seventh century. They would have been travelling between St Columba’s monastery on the island of Iona and the monastery at Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumberland. They may have established a monastery at Abbey St Bathan’s, which is named after Baithéne, Columba’s successor as abbot of Iona. In about the twelfth century a Cistercian nunnery was established here – hence Abbey St Bathans. Gaelic-speaking monks may also have founded the church at Bunkle, which probably means either ‘church at the foot (of a hill or escarpment)’ or ‘original church’, from Gaelic bun ‘base, foot’, and cill ‘church’. Another possible Gaelic place-name is Longformacus, perhaps meaning ‘the encampment of Maccus’, from Gaelic longphort and the personal name Maccus.

Valleys along the upper reaches of the Whiteadder were used for summer pasturage from Northumbrian times and probably before. Penshiel means ‘summer pasturage in the pan-shaped valley’, from Old English panne and scēla. Old English scēla became Scots shiel and shieling, referring to summer pasturages and the huts that stood on them. Shiel features in many names around the Whiteadder, including Dronshiel ‘shieling of the ridge’, Kidshiel and Stoneshiel. Gamelshiel belonged to a man with the Scandinavian name Gamel, which was adopted into Scots – 26 people called Gamel are on record in Scotland between 1124 and 1296.

After the Norman invasion of England in 1066, Anglo-Normans moved north into Scotland and founded monasteries which specialised in wool production. Shielings in the Lammermuirs were given to the abbeys of Kelso, Melrose and the Isle of May – hence the name Mayshiel. Place-names inspired by the presence of monks include Priestlaw and Friar’s Nose: these were hills near Penshiel, which was held by Melrose Abbey. Nunraw further north was Scots ‘nun’s row’: it belonged to the Cistercian nunnery in Haddington.

Friardykes was another farm held by Melrose. Recorded as frerdykis in 1479, the name meant ‘ditches or walls of the friars’. This name attracted colourful local legends. The Ordnance Survey Name Book of 1853-54 related: ‘It is said that a refractory Monk or Friar from the Monastery of Melrose was exiled to this place by the superior for disobedience and a wall or dyke had been built to enclose the portion of land which was allowed him, hence the name Friardykes.’ Another fanciful story involved a monk from Friardykes murdering a nun from Papple.

Scots has many terms to describe hills and other landscape features. Law is the general-purpose term for a hill, but can also describe distinctive, isolated hills such as Traprain Law. Other hill terms include dod ‘a bare round hill’, edge ‘the tilted slope of a hill’, kip ‘a sharp-pointed hill’, knowe ‘a knoll or subsidiary top’, and rig ‘a ridge’. Then there is cleugh ‘a narrow gorge’, hope ‘an enclosed upland valley’, lee ‘a sheltered position’, and shaw ‘a small wood’. Two body parts, nose and snout, refer to protruding pieces of land, as in Friar’s Nose.

To these are often added animal or bird names: thus Cow Cleugh, Crow Cleugh, Dog Law, Hare Cleugh, Hog Rig (a hog is an unshorn yearling sheep), and Rook Law. Horseupcleugh was Horshop in 1492, ‘an enclosed upland valley associated with horses’. A yad is a broken-down mare: Yadlee was on Dunbar Common and said to be where people from Dunbar sent young horses and old mares during the summer. Some names refer to the land: thus Meikle Says Law and Little Says Law may refer to saes or tubs, here meaning water-filled holes in the blanket peat. Hungry in Hungry Snout means that the land was poor.

Some names are deceptive. The settlement-name Elba looks like the island to which Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled, but began life as Scots elba ‘elbow’, describing a bend in the Whiteadder Water. Crystal Rig, now the site of a windfarm, was Kist Hill in 1799. Kist means ‘chest or coffin’ in Scots, and probably referred to the prehistoric cairn on the hill, known today as the Witches’ Cairn. Also on the hill was a well, now filled in, which local people believed could cure scurvy. It was called Kisthill Well in 1791, but later became Crystal Well.

An intriguing name is Danskine, on the Gifford to Duns road. There used to be an inn here, with smugglers of gin and brandy reputedly among the patrons. It seems likely that the name was a witty reference to the Baltic city of Danzig (Gdańsk in Polish), which was a major trading port, listed as Danskin(e) in Scottish shipping records. The village of Gifford developed in the late 17th century. Its name probably acknowledges the Giffard family from Normandy, who were given the Yester estate by Malcolm IV and his mother Ada de Warenne in the 12th century and held it for nearly 200 years.

Names often highlight the ancient sites which dot the landscape. Names with Scots stanes ‘stones’, here and elsewhere, often point to a stone circle, such as Nine Stones and Crow Stones. In the 18th century, the term castle was often applied to prehistoric forts, so we have White Castle, Green Castle and Black Castle. Castle Moffat may have been a hillfort site, but none can now be identified: the ‘tower house’ here is in fact a 19th-century construction.

Packman’s Grave was a popular name for single stones or groups of stones, with the legend attached that a travelling packman or pedlar had been murdered there. The stone setting at the fork in the road at the north end of the Whiteadder Reservoir is said to be the grave of a packman murdered by an innkeeper at Danskine. Truly the place-names tell stories, some truer than others!

Acknowledgements

Warm thanks are due to Peter Drummond, Carole Hough, Alan James, Bill Patterson and Simon Taylor for information and advice. Also to Deborah Campbell and Val Wilson for help with investigating sites. The online Berwickshire Place-Names Resource was an essential source of information. All errors are the author’s responsibility.

Photography by Liz Curtis

Map extracts from the National Library of Scotland

Further reading

Peter Drummond, Scottish Hill Names: Their origin and meaning, Scottish Mountaineering Trust, revised edition 2010, 1st pub 1991.

John Martine, Reminiscences and Notices of the County of Haddington, East Lothian Council Library Service 1999.

Links

The Berwickshire Place-Name Resource https://berwickshire-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk/

Berwickshire Ordnance Survey Name Books https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/berwickshire-os-name-books-1856-1858

East Lothian Ordnance Survey Name Books https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/east-lothian-os-name-books-1853-1854

Scottish Place-Name Society https://spns.org.uk/