During the first week of February, archaeologists and volunteers descended on the Bothwell Water Valley to undertake some targeted excavation of a previously unrecorded long building visible on the Whiteadder LiDAR survey.

The building measures approximately 50m long x 7.5m wide and consists of low turf covered banks of at least 1m wide with fairly straight sides and rounded ends. It is situated amongst a known area of rig and furrow cultivation, which had presumably masked the identification of the building on aerial survey since both the cultivation and the building are on the same alignment.

The valley is rich in archaeological remains mostly consisting of small pre-improvement settlement remains and agricultural features. The nearest known archaeological site is ‘Birk Cleuch’; a pre-improvement farmstead recorded on Roy’s Military Survey 1747-55 and recorded by the Scotland’s Rural Past Project, lies c400m to the south west, on a terrace overlooking the valley below.

The agricultural features primarily consist of cultivation remains and several structural features pertaining to the management of sheep, particularly sheepfolds and ‘sheep houses’. The sheep houses of the Bothwell Water Valley are interesting as they are visible on the OS maps as roofed rectilinear buildings, often with an outer enclosure.

(c) Trustees of the National Library of Scotland

Two trenches were opened at the Bothwell long building to see if we could ascertain the date, character and function of the building. They were placed across different parts of the structure to try and understand the construction of the walls or banks and any internal features.

The excavations revealed the remains of a surprisingly well constructed stone and turf wall forming the main structure of the building. The wall (pictured below) measured 0.8m wide and survived to a height of 0.75m, or three courses. It had suffered significant collapse, resulting in the interior of the building being infilled with a wealth of large sub rounded and sub angular stones as well as degraded turf and soil.

To the southwest of the main building in trench 1 a further wall was encountered. This wall had a different construction, similar to dry stone wall technique and appeared to form an additional annexe to the main structure.

Unfortunately no internal features or finds were present in the interior of the building. However, a curvilinear feature was cut into the subsoil below the level of the building, the fill of which contained occasional charcoal fragments. Samples were taken of the fill in the hope of obtaining a date for this feature.

On the basis of the excavated evidence, further research and contributions by Peter Corser of Historic Environment Scotland, we believe that the Bothwell long building is most likely a medieval sheepcote and possibly even belonged to the monks of Kelso Abbey, who likely owned this part of the valley.

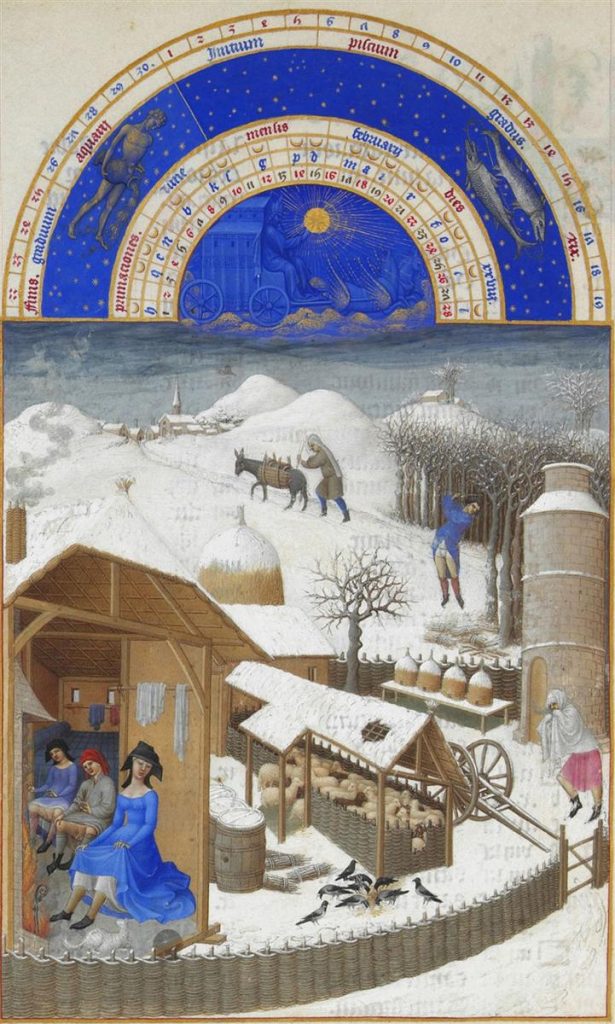

Appearing as the latin ‘bercaria’ in documents from the 12th century in England, sheepcotes were buildings constructed for the shelter of flocks and continued to be used through the latter medieval period (Dyer 1995). Depictions of them can even be found in medieval manuscripts such as the one pictured below from the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry from the 15th century, depicting sheep packed inside a long narrow building during the month of February.

Although many might consider sheep houses to be a relatively insignificant form of archaeological site, they can provide us with keen insight into the importance of sheep husbandry in the medieval period.

Sheepcotes were primarily for the shelter of sheep, particularly in the winter months. A well known medieval agricultural writer in the 13th century, Walter of Henley, advised that sheep must be housed from ‘Martinmas until Easter’; 11th November until March/April (Dyer 1995). However, they were also used for lambing, but also for the storing of fodder and equipment pertinent to the management of the flock (this storage is perhaps the function of the annexe at the Bothwell Long Building). Landowners often spent large sums of money on the construction and maintenance of their sheepcotes and punishments were enforced for the non-upkeep of structures and misbehavior of shepherds meant to be on duty with their flock; further emphasising the importance of sheep husbandry in the medieval period, and likely explaining why this seemingly mundane building was so well constructed.

The excavations at the Bothwell Long Building have served to further emphasise the importance of the valley’s examples of pre-improvement landscape; and serving as a reminder of the long lived practice of sheep husbandry in the region. How exciting!

Many thanks to everyone who volunteered their time and energy to help us explore this fascinating site, which we believe may be the first of its kind to be excavated in Scotland.

References

Dyer, C. (1995) Sheepcotes: Evidence for Medieval Sheepfarming. Medieval Archaeology 39:1, 136-164