Castles are, without doubt, among the most compelling icons of the medieval period. But not all were as impressive as those we see operating as major visitor attractions today, and few survive so well. The earliest castles were wooden motte and bailey constructions dating to the 11th to 13th centuries. This style of fortification was introduced after the Norman Conquest of AD 1066 not only as a defensive site but as a show of power and status. The word ‘motte’ is derived from the Old French for ‘mound’ onto which a tower was built. An embanked enclosure containing additional buildings – the bailey – often (but not always) adjoined the motte. The stone castles which we see today date from the late 12th century onwards. The move from timber to stone was made not only because timber castles were more susceptible to fire, but because stone was more expensive; using it to build a castle demonstrated the wealth and power of the elite for all to see. The most basic of these castles consisted of a stone keep surrounded by a bailey, although many were more complex. Where traces of these castles survive today, they rarely retain the designed landscapes – parks, gardens, orchards and so on – which were, in many cases, afforded as much effort as the design of the castles themselves.

Tower houses were typical residences of the Scottish nobility in the medieval period; there are almost a thousand confirmed or suspected tower house sites in Scotland today although many are in ruins or lost altogether. Others are lived in today, although in most cases they will be almost unrecognisable from their medieval appearance, whether due to significant additions over the centuries to form a much larger residence or indeed a castle, or more minor alterations such as the addition of harling. Smailholm Tower, near Kelso, is a fabulous example of a medieval tower house. It stands high on a rocky outcrop with commanding views all around.

Our project area boasts the remains of numerous castles, some still lived in today and others lost reduced to mere traces in the landscape. One such ‘lost’ castle is Morham Castle, recorded in The New Statistical Account as dating back to at least the 12th century. Nothing is visible on the ground today. Edinburgh Archaeological Field Society carried out geophysical survey in 2013 and 2014 which identified a series of anomalies. Excavations were carried out as part of this project and a substantial curving stone wall was revealed, at least 2m thick at its widest point. It is interpreted as part of a large tower wall or curving stair tower. Artefact finds suggest occupation of the site from the 12th to 18th century. You can read more about our excavations here.

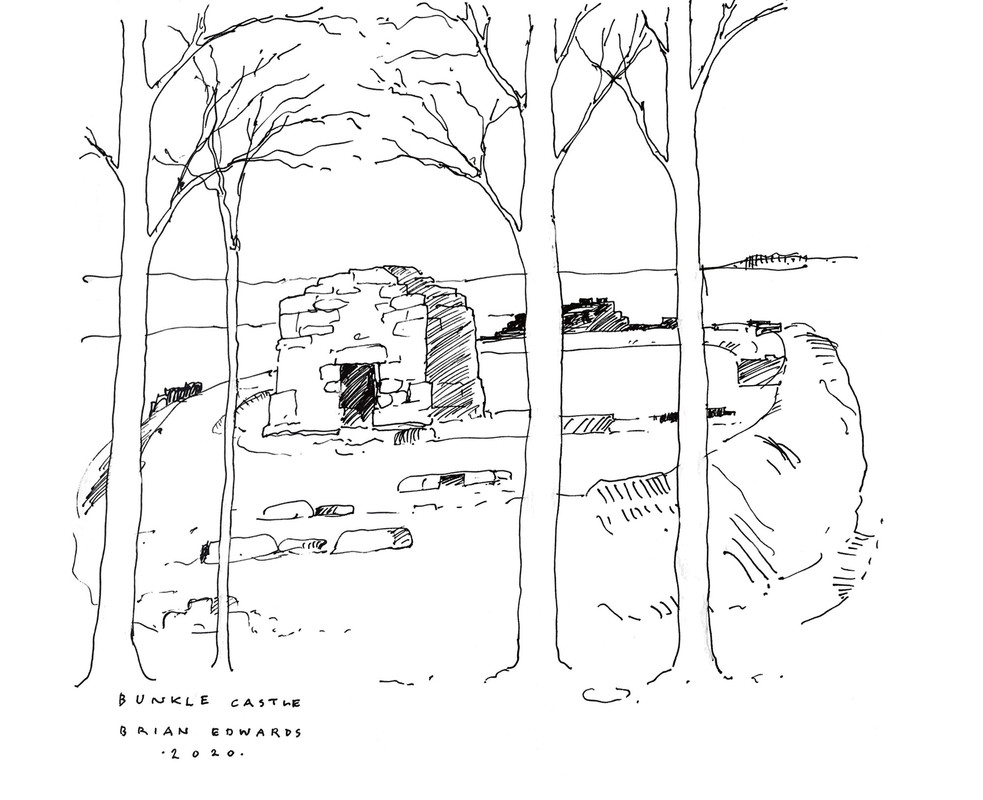

Bunkle Castle

Bunkle, or Bonkyl, Castle is among the oldest of the castles and tower houses within our study area that are still visible today (below). It is believed to have been built by the late 11th century. Little survives above ground today: only the fragmentary remains of a stone curtain wall atop a circular earthwork, or motte, on a natural knoll. The remains of a ditch or moat are visible around the base of the earthwork. Excavations in recent years revealed evidence of a probable fish pond in the field below the remains of the ruinous castle. Fish ponds were popular from the 11th century, created by the elite for the breeding and storage of fish both for the table and to sell. The consumption of farmed fish was a luxury not available to everyone, but it seems that the residents of Bunkle Castle may have enjoyed an extravagant diet: the discovery of a waterlogged grape pip indicates that they also ate imported (and expensive) dried fruits.

Billie Castle

Billie Castle is recorded as having belonged to the Dunbars at the beginning of the 13th century, passing to the Anguses in 1435. The ruinous remains (right) now form an uneven grassy mound within a ditched enclosure, which may once have been filled with water. There are traces of a number of stone buildings, including what may be a tower and gate-house. It is recorded that stairs in the northwest corner of the main building, and a round tower at the south, were still visible as recently as the mid/late 19th century.