In February, we headed back out into the field to explore a couple of sites, one in Abbey St Bathans and a second nearby, on the other side of the valley. AOC’s geophysical survey team came up from Leeds to conduct geophysical surveys, and to provide another opportunity for training – many thanks to everyone who came out and participated.

Our main target as part of this phase of work was in Abbey St Bathans itself, close to the site of a supposed early Christian chapel (read more about it here). The Whiteadder wends it way through Abbey St Bathans, a small, secluded village around five miles north of Duns. Abbey St Bathans is named to commemorate Baithéne, also known as Baoithin or Buadan, an Irish monk who briefly succeeded Columba as abbot of Iona in AD 697 before his own death in AD 698. Abbey St Bathans was formerly the site of a Cistercian nunnery, founded in the late 12th/early 13th century. The current kirk (now in private ownership and no longer functioning as a church), though much altered/added to in the medieval period and later, retains elements of the original priory church. Around 250m NNE of the supposed chapel site is St Bathan’s Well, a spring traditionally believed to have had healing properties.

The remains of a stone-built structure known as St Bathan’s Chapel lies around 500m SSE of the kirk, in a field long known as the Chapel Field. The site is mentioned in the Old Statistical Account, which records that the foundations of the chapel and an enclosing wall had “been removed on account of the obstruction they presented to the operations of agriculture”. Drainage caused the ruinous remains to be exposed once again and they were excavated in 1870. The supposed chapel was found to measure 11.6m by 4.7m internally, with what was interpreted as a small chancel at the east end (not visible during a visit in 1915 by RCAHMS). It has long been assumed to be an early Christian site but its origins and date are not clearly known. A feature interpreted as a stone coffin was discovered around 30m north-west of the chapel but no human remains were found. The chapel is not believed to have had an associated cemetery.

The chapel site is now much overgrown and in 2016 it was cleared and partially excavated by volunteers under the direction of Richard Carlton of Newcastle University. The building’s outline was revealed again but no traces of floor surfaces were encountered. The focus of our work, however, was not the chapel itself but the land around: based on the topography, we wondered if geophysical survey might reveal traces of a vallum (a type of enclosure often found associated with early Christian sites), for example, or any other archaeological remains that would help us explore the origins of the site.

AOC’s geophysical survey team undertook surveys (gradiometer survey and earth resistance survey) in Chapel Field in February 2020. Numerous anomalies were identified which may have been of archaeological origin. Most of these were linear in form, including one which was interpreted as a possible road or track. We opened three trenches targeting numerous of these anomalies, to examine their origins. Unfortunately, the result was…. an array of field drains! Old ones, newer ones, drains with ceramic pipes, drains lined with stones…. And none of them helpful at providing further information about the supposed chapel site. We were most disappointed but cheered ourselves and our dedicated volunteers up with coffee and cake (formally recognised as fuel for any community archaeology project) from the local bakery.

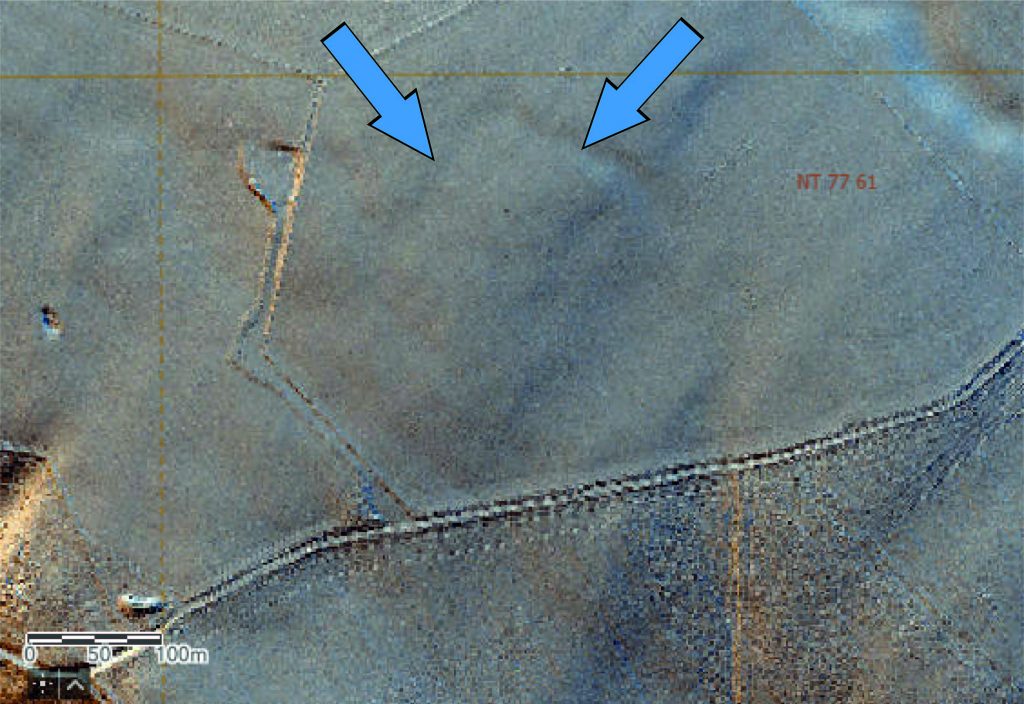

The second site we explored was a possible enclosure identified in the LiDAR data. The archaeological team analysing the LiDAR data were intrigued by an apparent anomaly at Blackerstone (below). There appeared to be the trace of a rectilinear feature on a high plateau on the other side of the Whiteadder; a prehistoric enclosure, perhaps? A site visit confirmed that nothing was visible on the ground so we moved onto geophysical survey to seek more information. The results of the survey were encouraging and suggested that there might even be some circular features (roundhouses, we wondered/hoped?) close to the large anomaly. Based on the geophysical survey, we had a mechanical excavator open a trench over the possible anomalies to explore further, while our archaeologists looked on, keen to see what appeared. Unfortunately there was nothing of archaeological interest to discover! Despite our disappointment, this is a result in itself since it contributes to growing understanding of how to interpret LiDAR and geophysical survey data.

While negative in archaeological terms, the results of both projects are important contributions to our understanding of how archaeological remains present themselves in remotely-sensed data, and how to interpret them, and archaeologists continue to learn how best to do this. But bear with us and watch this space because the next two excavations we undertook were corkers, and we’ll share more information about them as soon as we can!