While much of medieval agricultural activity left little trace on the landscape, evidence of farming – and its families and communities – after around AD 1600 is much more apparent. Farmsteads formed of clusters of homes and outbuildings are scattered across the landscape, their ruinous remains frequently still discernible. Townships were associated farm buildings and land held by two or more joint tenants, who usually worked the land together as a community. Sheepfolds in their many forms adorn the hills, almost 300 of them within the study area (read more here). Arable farming left its traces too, such as the undulations in the landscape caused by rig and furrow cultivation.

The Agricultural ‘Improvement’ movement of the late 17th to 19th centuries saw farming become more intensive, with semi-communal farming models being replaced by large, single-ownership farms. The unenclosed, reverse-S-shaped field systems produced by rig and furrow cultivation were replaced by more regular fields defined by walls, hedges or, later, wire fences.

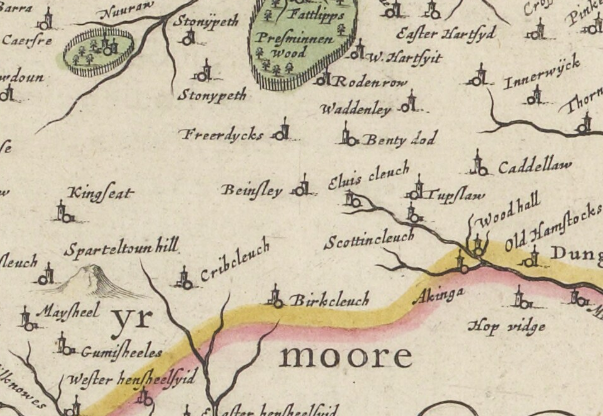

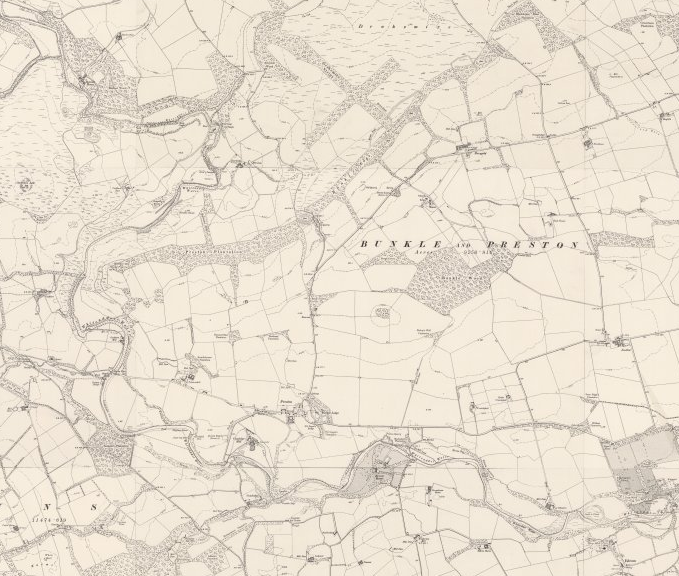

Compare Roy’s mid 18th century map of the Lowlands with the OS six-inch map 150 years later (below), and the difference is clear to see: just north of Duns, you can see that open landscapes have been transformed by neatly divided fields. You’ll notice too that significant swathes of forestry have been planted, a movement motivated on the part of the Improvers partly by aesthetics but also to offer protection from the wind as well as tackling the shortage of timber in the Lowlands of Scotland.

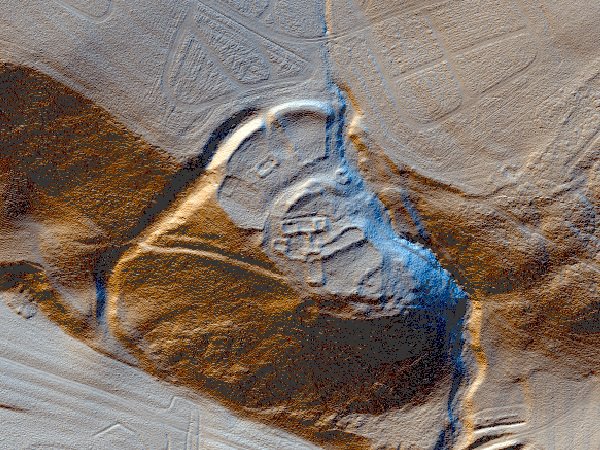

One farmstead, on a promontory low on the south-west flank of Wrunklaw, demonstrates neatly how desirable locations were selected through the centuries. The same spot was selected as the ideal building place on no less than three occasions. The earliest site there is a prehistoric fort. On top of this a farmstead was built, probably late- or post-medieval in date, and certainly ruinous by the time of the survey for the 1st edition OS 6-inch map, published in 1862. The same location was selected again for a shepherd’s cottage in the early 19th century. The farmstead as marked on the map comprised at least two buildings and an enclosure, although it’s likely to have been more complex than this.

Little remains now of what must once have been a busy community at Boonslie. A township, comprising ten buildings and associated enclosures, is found on a river terrace to the west of the Boonslie Burn on the northern edge of the Lammermuirs. Lengths of banks, perhaps head-dykes (used to separate the agricultural land of a township from rough grazing), are visible well as areas of rig and furrow cultivation.

After detailed survey, four possible phases were identified in the composition of the township, indicative of evolving occupation and usage. Boonslie (‘Beinsley’) is depicted on Blaeu’s Atlas of Scotland (1654) and on General Roy’s Military Survey of Scotland (1747-55) (‘Bunlay’).